Actually I wanted to call it The Sower II – Revenge of the Sower.

But then I realized that these stupid jokes were better left unsaid.

Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time – Year A

In this case the readings revolve around a main parable, which once again presents Jesus as the Sower, introduced by short passages which explain how God brings together his perfect justice and his unique mercy, accompanied by the insertion of two very short parables.

The Kingdom of God seen as a small mustard seed that grows into a large tree, and again: the Kingdom, or the Church, like leaven, which, despite being a small quantity, makes the whole dough grow.

But let’s get to the main parable. Presented in the liturgy a week after what I feel like calling the previous episode (they are found one after the other in the Gospel of Matthew), it has the Sower as the protagonist again; and again Jesus has to explain it explicitly to dispel doubts.

But reading them in parallel may baffle you. Last time in the explanation I had relegated Satan to the role of an extra. But now he appears not only as an actor, but as the antagonist and also co-author. Far from being independent of him and his actions, it seems that the wicked (symbolized by the weeds), who will be burned as waste in the eternal fire, are actually his children: they appear to be what the evil one has sown.

Alright, in the end the antagonist is defeated and the good harvest is collected. But what about those wretches destined to the eternal fire?

First of all, here’s a result.

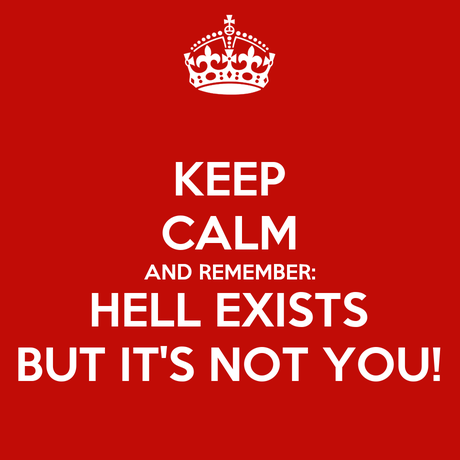

Newsflash: Hell exists!

This is for those numerous few who don’t want to believe in it, or who absurdly claim that “it must be empty”. As if God were one of those modern parents, incapable of asserting their authority, issuing an inherently empty threat, which everyone knows will never be acted upon. A joke. No, this is explicitly mentioned here: a

fiery furnace, where there will be wailing and grinding of teeth.

No kidding!

But there’s another aspect of hell which must be underlined, as it helps us, as I already said last time: the very presence of Satan lets us understand that we aren’t the ultimate authors of evil. And in this case explicitly, given that we’re dealing with sowing: even what seems to us most innate, ineradicable, within us from birth… If it is evil, it’s not really us; instead, it’s a seed that comes from the author of evil, from the first rebel.

Therefore we can treat it as a weed, to be thrown away.

Now I’d say this concept, if we take heed and treasure it, represents a nice and wholesome teaching to keep reflecting on.

You may remember that meme from some time ago:

God exists but it’s not you, relax!

Here, with a slight modification I think it could be said, using an image from an even earlier meme:

I think this concept may come in handy even if you’re a non-believing psychologist.

We are not the perpetrators of evil, but neither are we the punishment. The dark abyss is not in you, it’s not your life.

If God created you, and is a God of Love… it cannot be you, just you, personally, identified with the evil you may have inside. By the same token, you can’t be a child of evil in some way, or the cause of evil. Nor is the punishment in you. You aren’t wrong, you don’t have to hurt or punish yourself. Even your deepest anxieties come from outside. You just need to try and free yourself from evil, as best you can, one step at a time. Evil is something else, you can always be the wheat that grows and bears fruit.

Your essence is a gift from God, and it is good; it just has to get rid of this polluting waste too.

Okay.

But let’s go back to the problem, which is still unsolved.

Are some people predestined to go to hell?

Indeed, being sown by Satan would seem to indicate that they are not even (!) children of God…

Wait a moment. Let’s put things in order.

Jesus explicitly tells us who the reapers are: the angels who intervene at the end of the world to implement God’s will, throwing “scandals” (in the translation I used as reference, but your official USCCB version has “all who cause others to sin”) and evildoers into the furnace, thus implementing the Final Judgement.

But there are others, distinct from the reapers, that are called servants.

These servants would like to uproot the weeds immediately, without waiting for the time of harvest.

Even if it wasn’t part of the explanation, this reference is clear: these are believers who wish to judge and act during the life of the Church, before the end. They think they’re able to decide who the good and the bad guys are.

Jesus forbids doing this, because till the end we would not be able to distinguish, to separate the wheat from the chaff (which is a weed that closely resembles wheat).

This too is a fundamental message: do not judge!

However, the answer is still incomplete: is it just us, from our limited perspective, who don’t know who the chosen ones are and who are those destined to damnation, or is it a game that has to be played out through life?

It is precisely passages like this that inspired Protestant leaders, such as Martin Luther first of all, to inflict the doctrine of predestination on their followers. Such doctrine should still be part of the core doctrine for, at the very least, Lutherans and Calvinists, and perhaps that partly explains why you don’t see so many Calvinists around. As for the Lutherans, perhaps they are too busy chasing after the latest ideological trends to worry about the contents of their old doctrine.

Free will vs. Protestants

Yet that would be their (dreadful) frame of reference. Luther writes in De Servo Arbitrio, against the reasonable thoughts offered by Erasmus of Rotterdam:

the human will is like a beast of burden. If God rides it, it wills and goes whence God wills […] If Satan rides, it wills and goes where Satan wills. Nor may it choose to which rider it will run, nor which it will seek. But the riders themselves contend who shall have and hold it.

When was the last time you heard a Protestant preacher proclaim something like: “Convert to Christ, to demonstrate that you were already created to necessarily, inexorably do so, and thus enjoy eternal bliss beside God. If on the other hand you’re destined to damnation, there’s nothing we can do: God in his wisdom decided to create you for the express purpose of subjecting you to horrible torments for eternity”?

It’s clear that to believe something like this spontaneously, with no prior indoctrination, it’s necessary to have a deeply disturbed personality, as in fact I understand was the case for Luther.

But for a reasonable person, who has acquired some firm points of the modern sense of justice (which is Christian in origin!) and has a fair level of knowledge, the fork could not be more clear-cut and certain: on the one hand there is the possible scenario where you can find at the same time God, Jesus Christ and free will; on the other hand the only alternative scenario is that of atheism, where a human being is a computer, passively executing the instructions of a software program.

Today, only those who don’t believe in God can believe in man as a being completely enslaved by his own destiny.

Forgive me if I don’t further develop this thought right now, but please believe me, there’s a lot behind it. If God wills, I will be able to illustrate these concepts in the future, perhaps in a book.

But the point, for now, is this: if I’m programmed for a purpose, everything is already written in stone and I can’t do anything about it, nothing makes sense. If, on the other hand, there is human freedom, an ability to act autonomously in some way (made in the image of God!) then my destiny is not sealed, I am the one entity actually doing my part, able to choose what will become of me.

When viewed in this light, the passage becomes something entirely different: did Jesus say that we are predestined, therefore he was an impostor and nothing we believed is actually true, or was he saying something else entirely?

In fact we have plenty of examples in the Gospel of a different perspective, whatever the Reformed may have to say on the subject. The call to conversion, the continuous examples of people who change their lives by choosing to do good, to follow Jesus: “Today salvation has entered this house!” (Lk 19:10)…

Even through parables, think of the fruitless fig tree (Lk 13,6–9): the unrepentant sinner is offered a new chance to repent and change, once again. Which wouldn’t make sense if you couldn’t change yourself.

No, there has to be a different explanation.

Our puny minds trying to grasp

The metaphor of the geometric projection that I used when I wrote on the Trinity comes in handy, again: we see reality from a limited perspective; we can simplify the picture by reducing it to one of its aspects, to at least get somewhere. Sure, by doing so we can’t see the whole thing anyway, but it’s the best we can do.

Projections that highlight different aspects seem incompatible to us.

In this case the perspective is that of eternity. In the parable in question, the Sower wants the servants to separate the wheat from the chaff at harvest time: this is the Last Judgment. Even for us, at that point, every chapter has already been written.

But in the eyes of God there’s never been a future yet to be implemented, there are no surprises. He creates men and for each of us there’s no moment in which he “doesn’t know yet” whether one will be saved or not.

This is a complex interlocking puzzle for us to put our finger on, but it stands to reason that, in parallel:

– in the perspective immersed in the flow of time, we can contribute and change things,

– in the vision of eternity, everything is clear and evident, the bad guys are the bad guys and the good guys are the good guys; either your place is in the good wheat, or it’s in the weeds.

But I’ll go a step further, in exploring a concept that I think most people avoid because it seems incongruous, disturbing. If you are bad, were you perchance sown by Satan, like chaff? And we’re back to the question: what is it, exactly, that is thrown into hell?

Jesus explicitly says here that two things will be thrown, as I have already written.

Scandals , and then those who commit iniquity.

There is little doubt about the latter. I looked up definitions from a biblical lexicon. The term used is ἀνομία {an-om-ee’-ah}. Whether we’re dealing with “violations of the law”, with “lawlessness”, or with “evil deeds”, the meaning is unequivocal: the condemned are the authors of such acts. People.

But scandals are something different.

What are those scandals?

Well, perhaps here we can appreciate why I felt like launching myself into this sort of foolish enterprise: I don’t know Greek, and I could get on the wrong horse (it’d be nice to be put in line by a real exegete every now and then, just in case). But I seem to be able to grasp the underlying message quite correctly, like a well tuned radio: I guessed a meaning, and as soon as I checked, I found confirmation that it was indeed so.

Here we have the plural of σκάνδαλον {skan’-dal-on}, which can indicate a trap, a stone one stumbles upon (which paradoxically in another context applies to Jesus himself), therefore any impediment that causes a fall. But also a person or a thing by which one becomes entangled, trapped, led to error or sin.

A range of meanings, well connected to each other; it’s complicated indeed. But I wanted to specifically emphasize a person or thing because here lies the essential element for the interpretation of the passage. And in fact different translations tend to alternately indicate one or the other! Once again, translating is betraying, as they say: to understand a text, we cannot limit ourselves to reading a translation, which reflects a partisan perspective, an imprecise or tendentious interpretation.

My approach to the text is one that respects the circumstance: while a modern exegete typically assumes that any difficulty in the text indicates a quality issue with the text itself, and consequently a lack of reliability, a very human aspect that makes you doubt the veracity of the testimony, I try to see if the very fact that those words came down to us in a certain way doesn’t mean something.

Here I think it is no coincidence that we are faced with an ambiguity. After all, if you’re not an atheist exegete, why should you think of a random occurrence? Can happenstance be found smack in the middle of a plan devised by the Almighty Being?

No. My interpretation is this: scandals are not people, they are all the things that lead us to evil: the seeds of Satan. But they are also, inevitably, that evil made real and present within us. They are “things”, but of the type most intimately intertwined with our personhood: they are in us, and they change what we make of us.

The gist of this all.

The Final Judgment involves purifying, gathering the good and trashing anything evil that was polluting the whole: these are the things that are thrown away. But immediately after that, there are also the people who are tied to these bad things, who chose to be workers of iniquity.

There’s an order of priority even in Jesus’ explanation: first the seeds of evil, then the people who identified themselves with this evil, who made it their life.

Scandals aren’t just weird things laying out there, in the wild. They are also part of us. Burning these weeds also means experiencing an inner, painful process: tearing apart, and that’s necessary to free ourselves. Well, if one dedicated his/her life to evil, starting from a bad place, then going lower and lower, it won’t be so easy to distinguish and separate that person, potentially called to beatitude, from that evil seed that has invaded and colonized him/her almost completely.

A further thought on the theme of projection. We shouldn’t think only in terms of individuals, because that’s a simplified projection (we’re used to) which is inadequate to describe the entirety of what we are. The harvest is a common good; for better or for worse we all participate.

The right question we must ask is not “where am I, personally: what place has been assigned to me”, but “how can I participate, bear fruit”.

In the end, this is the meaning. There’s chaff. “I am not those weeds” is all you have to think, striving to be good wheat instead. Then you won’t be a weed, even as seen from the eternal perspective.